The Forth and Clyde Canal runs from the River Forth in the East, to the River Clyde in the West. Fully opening in1790, the canal took 22 years to build. It is 35 miles long, crossing Scotland at its narrowest point, very close throughout its length to the Antonine Wall, The canal had 3 main functions: to provide a safe and quick route for seagoing vessels to transit between the east and west coast of Scotland; to transport locally manufactured goods; and to allow passengers to travel easily across the country.

The Glasgow branch was built in 1791 and the canal was joined to the Union Canal at Falkirk in 1822, providing a route from Edinburgh to Glasgow. It was built 60ft wide and 9ft deep and thrived for many years with much industry along its length. Eventually, of course, ships became too large to use it and decline set in.

We started Saturday’s walk on the Union Canal at the laughin’, greetin’ bridge. Built to span a deep cutting this splendid bridge has a carved face on each side, the one facing east, towards Edinburgh, is smiling but the one facing west to Falkirk is scowling. One explanation is that the contractor undertaking the easy section to the east became rich, whereas the construction of the tunnel and locks to the west caused the contractor to go bankrupt.

Walking towards Falkirk we soon entered the 690 yds. long Falkirk tunnel, built at the insistence of the local laird who didn’t want views from Callendar House spoiled by the canal. The tunnel is cut through solid rock, now illuminated with coloured lights along the offside which allows the walker or boater to view the impressive hewn rock (and the wet bits!)

From here it’s a short distance to the top of the old lock flight, where 11 locks joined the Union Canal with the Forth and Clyde at Port Downie. The upper quoins of the top lock are just visible and lock 2 has been partly excavated. It is possible to follow the line of the locks down to Port Downie but there is no more evidence of the locks or pounds to be seen so we returned to the Union Canal.

Passing Port Maxwell, the original terminus of the Union, which, despite it’s name always appears to have been just a dead end in woodland, we continued onto the new 1.5 mile section of canal, built as part of the Millenium link. New staircase locks drop the canal down to Roughcastle tunnel which takes the canal under the Antonine wall and the main Glasgow to Edinburgh railway line.

We emerged from the tunnel to the upper level of the Falkirk Wheel, a fantastic spot for a first view of the aqueduct that leads to the wheel with the Ochil hills beyond. A trip boat conveniently entered the wheel as we were admiring it.

The wheel (which is apparently based on the shape of a traditional two-headed axe) is designed to last 120 years, It takes a little over five minutes for a full rotation, and the direction is changed every few days to keep the wear and tear evenly spread. The wheel measures 35m across and can lift six boats at a time, consuming only 1.5 kilowatt-hours – enough to boil six to eight kettles.

This was a pleasant spot for lunch in the sun and to admire the wheel from different angles.

Refreshed we set off again to walk to the Kelpies and Grangemouth. In its heyday this section of canal was lined with chemical, iron and gas works, malthouses and a distillery. All but the distillery (unused and in danger for some time, this is now in the process of restoration) are gone and the canal makes for a very pleasant walk through Falkirk with tree lined sections and the Ochil hills always on the horizon.

There are 16 locks down to Grangemouth. Post Downie joins the canal just above the top lock. This was a large basin at the bottom of the flight from the Union canal, the entrance is still visible but the basin is infilled.

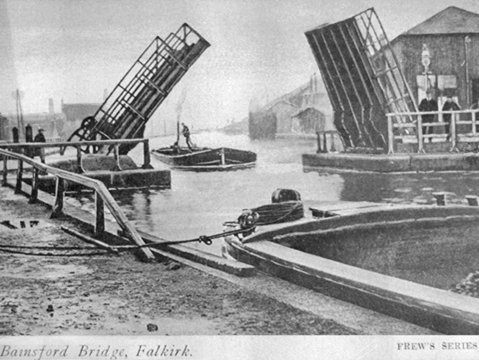

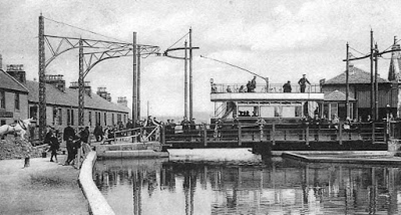

As part of the Millenium link locks 11, 8 and 5 had to be re-built upstream to get clearance under bridges, the old lock chambers still remain. Below lock 9 is a railway swing bridge, now fixed. At Bainsford, between locks 6 & 5, the bridge is in it’s 3rd incarnation. Originally a bascule bridge, it was replaced in 1905 by a heavier swing bridge to accommodate a new tramway and is now a modern, concrete road bridge.

Walking down to lock 3 the Kelpies came into view, appearing to emerge from the fields to our left. The original line ran straight on to the large complex of docks at Grangemouth. It now takes a 90˚ turn towards lock 3,the 30 metre high Kelpies with hills beyond make a stunning sight.

This new section of canal originally ran along the back of the Kelpies and a lock dropped the canal down into the River Carron, however the headroom of a bridge downstream caused problems. Now a new lock between the Kelpies drops the canal down into a circular basin and from here the canal runs a further half mile alongside the Carron to join the river further downstream.

A few of our group carried on walking down this link, others retired to the tea room or went in search of (very good) ice cream before returning to recover the cars. The end of a really interesting day with many points of interest, luckily we had blue skies throughout, showing the Falkirk Wheel and the Kelpies at their best.

After a rest and freshen up we gathered again at the canalside Stables Inn near Kirkintillock. The building is contemporary with the canal, originally providing stabling alongside an Inn. We were given a room to ourselves to enjoy good food and company before retiring.

Sunday dawned damp and windy but we all gathered cheerfully in Glasgow. Today’s walk started at Port Dundas, the terminus of the Glasgow branch. At one time a hive of industry with a large timber basin in the centre, it is now home to a watersports centre and we were treated to the sight of a waterskier practicing jumps near the old railway swing bridge. The bridge is now fixed open but the hand- worked cranking mechanism still remains. A wooden bascule bridge lies just beyond.

At the southernmost corner of the basin was the entrance to the Monklands Canal. Now buried under the M8, the 12 mile long canal provided both coal for industry and a water supply for the Forth and Clyde – a piped supply still flows along the former route.

A new section of canal had to be built to connect Port Dundas back to the Glasgow branch. As a road bridge crosses here a new lock drops down from the Port Dundas taking the canal under the bridge and into a new basin, another new lock then lifts the canal back up to Spiers Wharf. This new basin has good moorings, however boats aren’t allowed down into it!

Spiers Wharf was one of the early restoration success stories. An attractive Georgian building is the Old Canal Company office, next to this is an impressive range of 19th century buildings. Originally housing grain Mills and a sugar refinery, later used as warehouses, they were restored and converted into canal side flats in the 1980’s. The canal here is above the city centre and looking back there are excellent views to enjoy.

Next we came to Possil Road aqueducts. The original was too small for Glasgow’s tram network and a larger one was built in the 1880’s at the side to replace it – more aqueducts were built further up the arm to allow for the burgeoning tram system. Immediately beyond is Applecross Street Basin, the original terminus of the canal. The buildings here, which consist of warehouses and Old Basin House are probably the oldest on Scottish canals. Unfortunately they are in a pretty poor state of repair with saplings growing out of the windows of the warehouses. We thought it was a shame that they haven’t been restored and a new use found for them.

Carrying on up the branch we soon saw the first of several wartime stop locks, put in to control flooding in the event of the canal getting bombed. We looked down the embankment at the towing path side of the canal and realised what a devastating effect a breach would have on all the buildings and busy roads below.

Passing the Hamilton slip, a former boatbuilders, on the offside we soon reached Firshill Basin, part of a large complex of timber ponds in which timber was stored afloat before cutting. Continuing the very pleasant walk to Stockingfield junction, where the Glasgow branch joins the main line, it was hard to believe that the canal runs practically alongside the very busy Maryhill Road.

For 2 years, during the construction of the canal, Stockingfield junction had become the terminus when money ran out. Once the canal was completed to Bowling Basin and the Glasgow branch built a floating bridge was installed at the junction to transfer horses from one towpath to the other. Here we turned left for Maryhill locks and the Kelvin aqueduct.

At Maryhill locks pounds between the locks were built very wide to try and prevent bottlenecks and a dock was built between locks 22 & 23. Originally for repairing vessels, in the 1850’s it became a boatyard. The Kelvin aqueduct was the largest of its kind in Britain when it was built, it almost bankrupted the canal company but became a big tourist attraction.

Aerial shot of Maryhill locks and the Kelvin aqueduct showing the wide ponds and dockAs the rain had turned heavy this group of tourists didn’t stop for the usual examination of such a structure but instead dashed for the shelter of the cars and some much needed food and drink at Wetherspoon’s.

The rain continued but luckily we were just driving to 2 sites in the afternoon. The first was Dalmuir drop lock, where a boat is let into the lock at one end, water pumped out, the boat moves under the modern road bridge to the other side and water is let back in.

Our final stop was Bowling Basin, where the canal drops into the River Clyde. Before the Clyde was deepened, all trade had to use the canal and the Custom house, dating from 1800, still overlooks the lower basin. There is also the original bascule bridge between basins and the impressive Caledonian Railway swing bridge.

We viewed these rather more quickly than we would normally and walked down to see the old and new sea locks before dashing for cover again – some to their cars, others for a very welcome hot drink and cake at the café.

An unusually fragmented finish to the weekend due to the deteriorating weather, but a thoroughly enjoyable and interesting one nevertheless.

Unfortunately this wonderful canal is facing the threat of closure (again). IWA recently reported:

Hot off the press is news of the announcement from Scottish Government on 28th June that additional funding of £1.6 million has been found to carry out repairs to Bonnybridge and Twechar lift bridges on the Forth & Clyde Canal, and also to carry out further work to Ardrishaig Pier (all issues that we have been campaigning about). We hope this will mean a swift reopening of the Forth & Clyde Canal as a through route from coast to coast across the Scottish lowlands.

We are, however, extremely concerned about the future of the Lowland Canals, following the recent publication of Scottish Canals’ Asset Management Strategy, which suggests that sections of the Lowland Canals could face permanent closure.

The Forth & Clyde and Union canals were restored as a Millennium project, with funding from the Millennium Commission, European Regional Development Fund, Scottish Enterprise and local authorities. The Millennium Commission and European grants included conditions that the canals must be maintained to cruising standard for up to 25 years. The canals were reopened just 17 years ago.

As recently as 2011 the Scottish Government re-classified the Lowland Canals as Cruising Waterways, thus placing a statutory duty on the Board to maintain them for cruising vessels, in order to protect the investment made in restoring them.

Scottish Canals argues that the Lowland Canals are not being used sufficiently to justify keeping them open, but a lack of dredging and poor maintenance – together with recent closures and restrictions – will have contributed to a reduction in use. In our view the level of use should not be a significant factor in whether or not a waterway is kept open, as a vibrant waterway is kept alive by boats using it, and this in turn brings benefits in terms of improved health and wellbeing for the local population, as well as income through recreation, tourism and regeneration.

Scottish Canals should be doing everything it can to keep the Lowland Canals fully open, and this should include using some of the revenue raised from their property and tourism investments, which is currently not being spent on the core function of maintaining the waterways, despite an expectation from the Scottish Government that it should do so.