We started the walk on the Huddersfield Broad Canal (originally the Sir John Ramsden canal as the Ramsdens owned the area at the time) at the locomotive lift bridge. When the canal opened in 1776 to link Huddersfield with the Calder and Hebble navigation there was a swing bridge here, or turn bridge as it was known locally, the road approaching it being called ‘Turnbridge Road’. This is somewhat confusing these days with the bridge now being a lift bridge. The very impressive and unique locomotive bridge, built by the London and North Western Railway Co, replaced the swing bridge in 1865 and is a scheduled ancient monument. (Thanks to Gerald for the information on the Huddersfield Broad and the Locomotion Bridge).

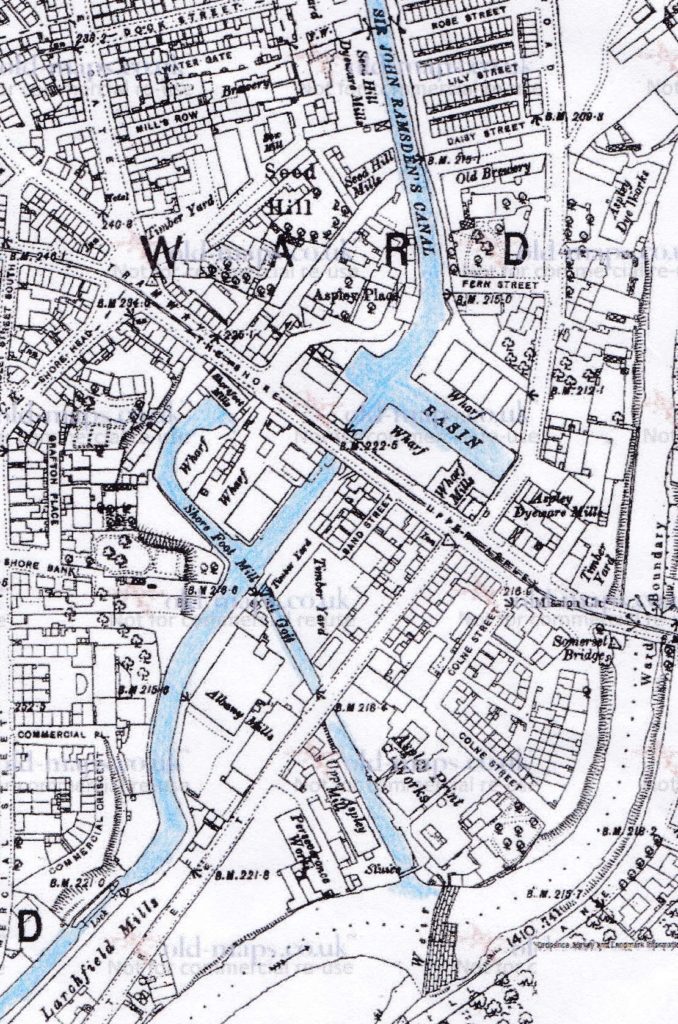

Having admired the bridge we moved on to our first stop at Aspley basin where goods coming over the Huddersfield Narrow would have to be transshipped to continue on their way due to the shorter, wider locks on the Huddersfield Broad. The A629 dual carriageway runs next to the basin and was one of the culverted blockages hindering the restoration. This was rebuilt during the major works of 1999-2001 (more of that later) although boaters beware – the headroom is pretty limited.

On the other side of the bridge is an attractive stone warehouse, complete with crane. After this it appears as if an arm runs off to the left, but old maps show that it was a goit bringing water from the nearby River Colne to serve Shorefoot Mill, situated at the end of an arm on the opposite side of the canal, and to feed the canal. Only a small section of the mill arm remains but a crane is still in situ.

On to lock 1E and the start of the Huddersfield Narrow.

Work started on the Hudderfield Narrow in 1794 with Benjamin Outram as engineer. Plenty of trade was anticipated due to the many woollen, worsted and cotton mills along the route. As they would all need water Outram proposed 10 feeder reservoirs for the canal. Progress was slow, partly due to Outram having too many commitments and being ill for a long period. Other setbacks included severe flooding in 1799 which damaged earthworks and various reservoirs, partly devastated the village of Marsden and destroyed two aqueducts, and the Black Flood of 1810 when Diggle Moss reservoir gave way, again flooding Marsden plus much of the Colne valley, wrecking houses and factories and killing five people.

Finally opened to through traffic in 1811, Telford having taken over construction of the tunneln the canal has 74 locks and the 5,700 yard long Stanedge tunnel, the longest and deepest on the system.

The canal saw moderate success but by the start of the first world war very little trade was left and in 1944 it was abandoned. Most of the locks were filled with rubble and concreted over to form a cascade, eighteen bridges had been culverted and nearly 2 miles of the canal filled in.

In 1974 the Huddersfield Canal Society was formed and they presented the local council with a comprehensive plan for restoring the canal providing solutions for all the blockages. With the local textile industry in decline the council agreed to protect the line of the canal recognising that the future of the area may be in tourism. The society was very active, attracting many members and much publicity for ‘the impossible restoration’. However, BW wouldn’t let work start until funding was found to maintain the restored lengths which eventually Greater Manchester county council agreed to do at Uppermill. Progress was slow until job creation schemes came into being, this speeded up the restoration and in 1988 the abandoned canal status was removed so navigation could return to the canal. However there were still several significant blockages hindering full restoration. With grants being given by the Millenium Commision and English Partnerships totalling almost £28,000,000 contractors moved in and the restoration gained pace, finally re-opening in 2001 but with only 2 of the original 10 reservoirs in use.

Our next stop on the walk had been one of the major blockages; just past the site of the original lock 2 the buildings of Bates and Co had been built across the canal. The solution to this was to lower the channel by 3 metres taking the canal through a tunnel under the building and relocate lock 2 upstream. The old lock and new deepened section of the canal being braced with beams.

As there is no towpath through the tunnel we followed the well signposted diversion on the roads round the Mill. On returning to the canal we looked back at the new lock 2 then crossed the road to what had been another major blockage.

Sellars Engineering had occupied the area of the former wharf and canalside warehouses. In the 1999-2011 works the canal channel was moved south of the original line, a new lock 3 built upstream and a 300 metre tunnel was built under Sellars. However in 2011/12 this changed. Sellars moved to a new site, the tunnel was opened up and lock 3 moved back down channel, closer to the original. The area around is being redeveloped with buildings for Kirklees College and Huddersfield University. The former tunnel section of canal remains a narrow.

Our original plan had been to carry on walking up to Milnsbridge but towpath improvements had shut most of the section from here to Milnsbridge so we returned to our cars and drove to Milnsbridge Wharf. Here emergency works had just been completed on lock 9 and CRT had provided us with the following information:

‘The problem with all the locks on the HNC is that water is leaving the chamber into the lock quadrants. Over the years this had washed away the fines within the quadrant and left voids’. The repairs involved ‘removing stone setts, digging down to a firm level, lining the void with terram, fill with pea gravel and re-laying the sets’.

Having examined lock 9 there was just enough time to look around Milsbridge wharf, where flats have been built that sit well next to the old stone mills that line the canal.

Then walk down to the interesting lock 8 where the towpath closure ended. Here a cameo of mills buildings surround the canal, the bridge below lock 8 has been widened and the bottom balance beams now protrude over a highish wall making lock working interesting, the iron lower bridge parapet is original and shows the earlier road line and there is an unusual bywash outfall below the lock.

Another short drive took us to Slaithwaite for lunch at the wonderful lock 22 café where we all sat in the sun to enjoy our substantial lunches before sampling the first ice-cream of the day.

The canal alongside the café had been infilled and covered with grass and cherry trees, just downstream lock 22 had been buried for 30 years under a car park. During the restoration this was re-instated. The channel is narrower than originally but this 600 metre section which runs alongside the main road through Slaithwaite is now a very attractive feature of the town, and popular area for visitors.

At the top end of this section the bridge below lock 24 had been widened leaving no space for balance beams, the solution here was to install a guillotine gate, this has presented some problems in recent years but is now back in working order.

From here the canal progresses through attractive tree-lined sections with elegant stone bridges. Between locks 26 and 27 was the dam for Shaw Carr Wood Mill. At some time this has been breached through to the canal and causes problems with siltation in the canal.

The route then emerges into glorious open hill scenery with the occasional stone built house and the remains of mill races running parallel – providing plenty of interesting diversions.

Sparth reservoir also runs alongside the canal. Because the canal was due to close due to water shortages two days after our walk, we had expected the water level in here to be spectacularly low, but this wasn’t the case and several swimmers and sun-bathers were taking advantage of the warm weather and beautiful location.

We finally arrived at lock 42E, the top lock on the east side of the canal, and next to Marsden Station. Here we split into two groups, one group carried on to the tunnel and visitor centre and those who had been before and therefore considered another ice-cream more of a priority dropped down into Marsden town centre for the ice-cream parlour.

With its restoration features, stone bridges and mill buildings, and the amazing views as it climbs into the pennines the Huddersfield Narrow remains one of my favourite canals. Walking the canal gives a different perspective to boating and it is well worth doing both if you have the chance.

By popular request a walk on the west side will follow….