The weekend started on Friday evening when we were met by Derrick Hunt and Patrick Moss from the Somersetshire Coal Canal Society who gave us an excellent talk about the history of the coal canal.

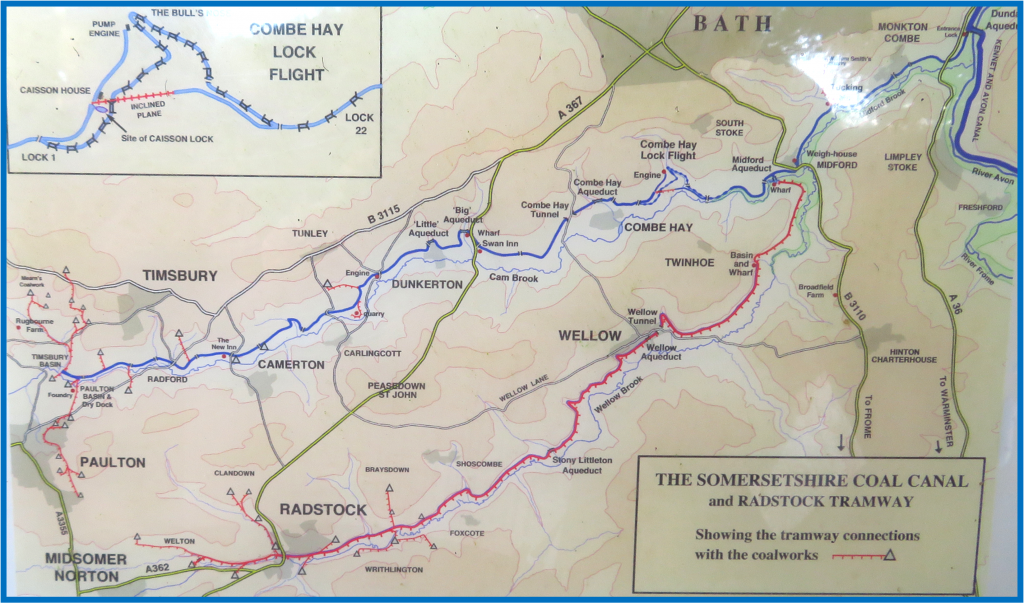

The name of the canal is self-explanatory, it was built to transport coal from the Somerset coalfields of Timsbury, Paulton and Radstock to Bath, Wiltshire and beyond. Coal had been dug in the area since the 15th century; by 1680 pits had been opened in the Paulton area and in Radstock in 1763. In the period 1680-1690 the Paulton pits were producing 100,000 tonnes per annum but transportation of the coal to the Bath area was difficult and expensive. There was serious competition from Pontypool coal as this was cheaper to transport to Bath. The solution was to build the 10½ mile canal from Timsbury and Paulton basins to Monketon Combe to join the Kennet and Avon canal at Dundas Aqueduct.

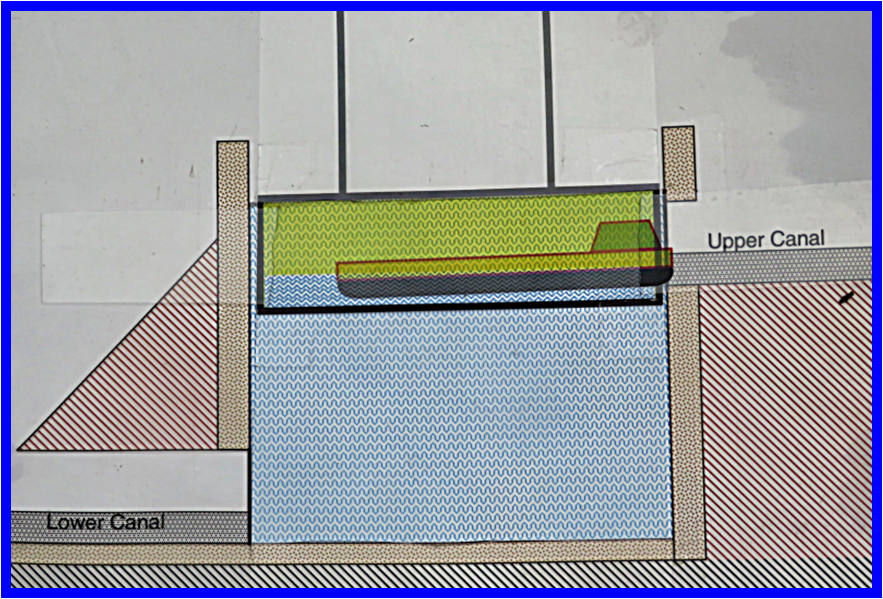

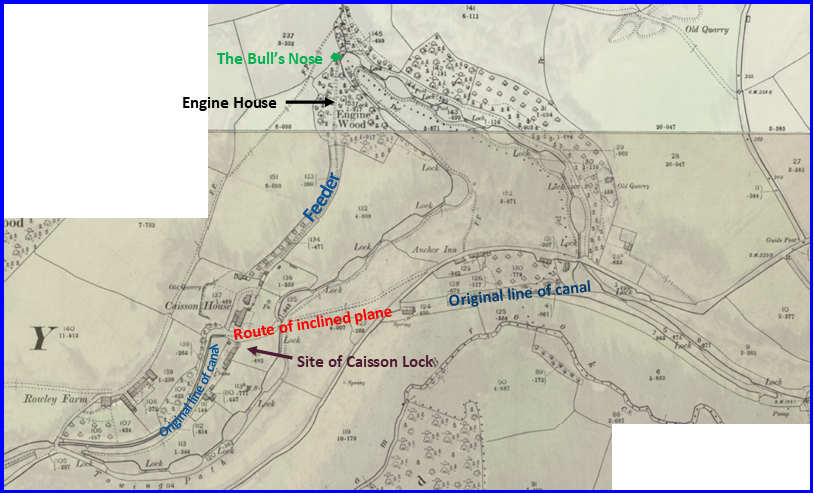

After a stop lock at Monkton Combe the canal ran level until it had passed through Midford then it had to be raised 135 feet to it’s summit level. A flight of 3 caisson locks were the first solution, a boat was floated into a water tight caisson completely submerged in a water filled masonry chamber about 50 feet deep where it could be floated up or down, saving water.

This system soon failed and was replaced by a gravity operated inclined plane which moved loaded carriages carrying boats between the bottom and top. Finally, a flight of 22 locks was built around a very tight bend in the hillside.

The canal was complete by 1805 and was very successful. Between 1812 and 1823 transported coal rose from 66,000 tonnes to 106,000 tonnes per annum and by 1858 this had risen to 165,000 tonnes per annum (over 8000 loaded boats). However, with railway competition by 1892 the tonnage had dropped to just 17,000 tonnes per annum and in 1893 the canal company went into liquidation. On 11th November 1898 the pumps at Dunkerton were decommissioned and the canal closed, after which the canal was bought out by the Great Western Railway.

Bath stone which is used for much of the old building in the area is very prone to frost damage. It is very porous and must be laid in the same orientation as it was in the ground (ie. top to top) to allow water to drain freely, otherwise frost damage occurs, clearly visible on many old structures, including Dundas Aqueduct.

The Somersetshire Coal Canal Society was formed in 1992 ‘to research, document and preserve the canal’ and have been busy restoring sections and preserving the line for future restoration.

On Saturday morning were met by Liz Tuddenham , who was to be our guide for the day, at the Somerset Coal Canal Visitor Centre at Monkton Combe. This is situated on the coal canal about 500 metres from the junction with the Kennet & Avon. Before setting off along the coal canal though, we walked along the Kennet & Avon to Claverton Pumping Station where we were given an excellent tour by Julian Stirling and his team along with former volunteer Neil Hardwick.

Originally a mill site, Claverton was the second pumping station on the Kennet and Avon. Crofton supplies water to the highest level of the canal but a second pumping station was needed at Claverton to top up the canal which had frequent leaks and the need to supply the Bath flight of locks.

These two excellent videos show the working of the pumping station:

Unfortunately the building floods every winter – some of the higher flood levels are marked around the archways inside – and soon after our visit the volunteers would be preparing it for the winter with the prospect of cleaning the silt out yet again next year.

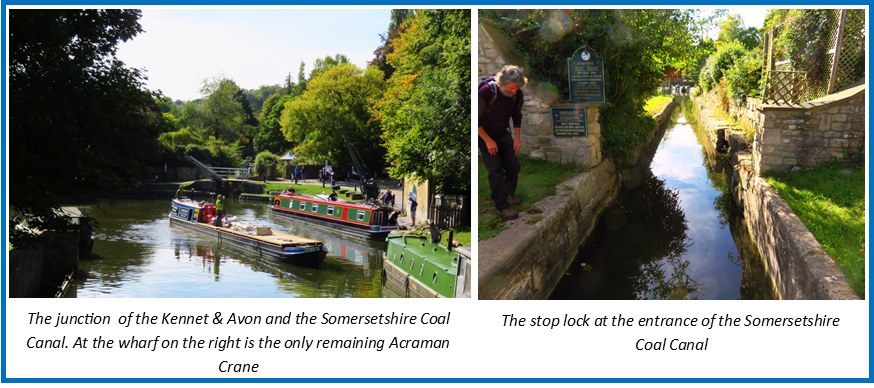

Retracing our steps along the Kennet and Avon we stopped to admire the last surviving example of an Acramans Crane situated at Dundas Wharf next to the junction with the Somersetshire Coal Canal. This was used to lift cargo and stone weights for calculating toll charges.

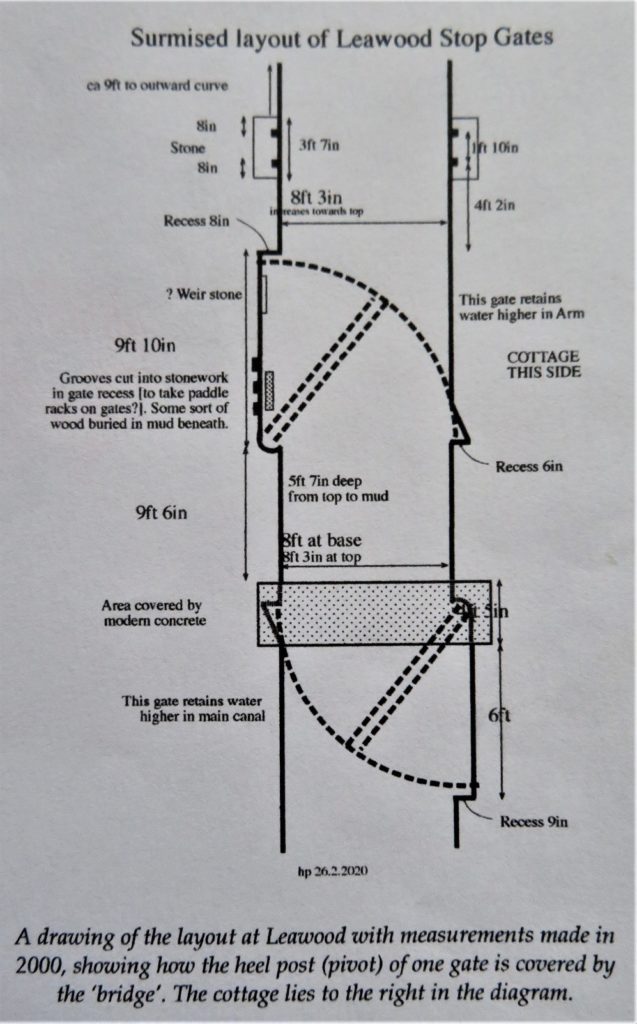

The entrance to the Coal Canal originally had a stone bridge which is long gone, an aluminium lift bridge was sourced to replace it. The stop lock had an extra gate in the centre of the lock which would close if levels dropped, to preserve the level on the Kennet and Avon canal. There is a theory that this was originally a wide lock as when it was excavated the invert of the lock was found to have a distinct slope from one side to the other, rather than sloping down to the centre as would be expected with a narrow lock. This may explain the possible position of a crane base at the far left corner of the original lock for lifting wide stop planks.

Before leaving the Kennet and Avon we had to stop and admire Dundas Aqueduct, completed by John Rennie in 1810 and now a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

We now joined the Somersetshire Coal Canal. The first section is in water and used by a boat business so a slight detour has to be taken around moorings. After the moorings is the visitor centre and café providing welcome refreshments. From here we started the afternoon’s walk to just beyond Midford. The in-water section finishes just beyond the visitor centre where it goes into a tunnel under the main road. The other end of the tunnel is blocked and the tunnel is currently being used as a wet dock.

Then next section of the canal is dry and various diversions have to be made. Immediately after the tunnel the Limpley Stoke to Camerton Railway cut through the canal, effectively cutting off most of the canal from the rest of the system. The footpath kept crossing the line of the canal until we reached the village of Monkton Combe where we diverted through the village. Luckily we found the village lock up was open for viewing so this provided an interesting diversion.

From here we followed the road to Tucking Mill, a small hamlet that had a wharf next to the mill. The hamlet is where William Smith, ‘father of English Geology’, lived after surveying the line of the canal, the blue plaque is placed on the wrong house in the hamlet!

We now regained the towing path of the filled in canal and followed it through to Midford where we had to make another slight detour round the Weigh House which is surrounded by high fences and trees. This building housed a machine for weighing boats rather than using the usual gauging stick so that tolls could be charged.

At Midford the Camerton and Limpley Stoke Railway cut across the canal with temporary lines having been laid on the towpath of the then derelict canal for moving materials to build the new railway. We carried on along the canal to Midford Aqueduct, the start of the Radstock Branch. where a canal was planned to transport coal from Radstock. This would have needed 19 locks and rather than continuing the canal a tramway was built with a canal basin across the other side of the aqueduct. The aqueduct was in poor condition and has been restored with the aid of Heritage Lottery funding.

A short way from here is the last surviving original bridge on the canal. This was the final stop for the day from where we retraced our steps to the car park.

Then followed an enjoyable evening at the Swan Hotel in Bradford on Avon. With a choice of classic British and Thai dishes the food was delicious.

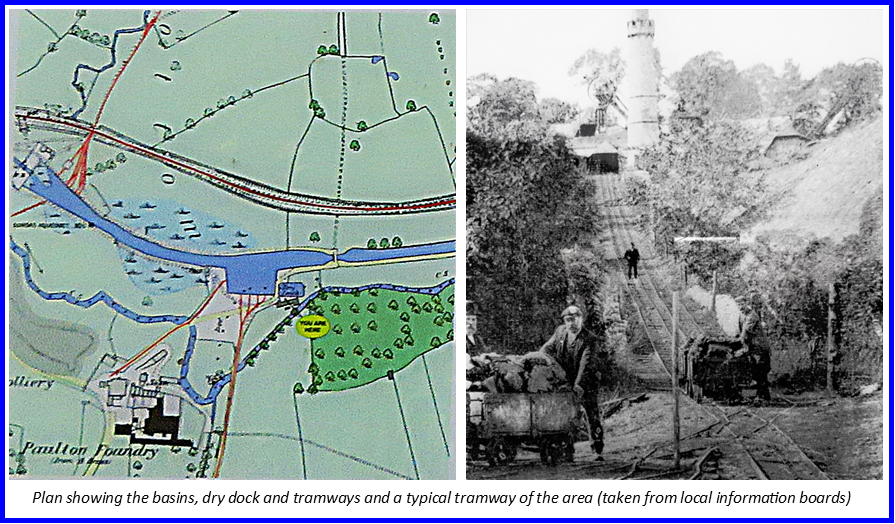

On Sunday morning Derrick along with Roger Halse met as at Paulton and took us down to Paulton and Timsbury Basins, access to which is down a lane and across a field.

Being used to terminal basins in towns and cities surrounded or obliterated by buildings it was unusual to see these basins in the middle of a field. The few buildings that stood alongside the basins are long gone but in one of the fields you can make out dark patches where the various tramways would have brought coal down to the basin from the coal pits. There was also a very large dry dock. Both the basins and the dry dock have been excavated by the society with the approval of the landowner and the basins are in water.

A short way from the basins there is a bund a cross the canal to retain the water as the next bridge needs rebuilding. This is a public right of way and the society are keen to restore it but currently there are problems to overcome with the landowner. We walked a little further along past the site of a stop gate to Withy Mills where there had been another colliery, tramway and a large wall is visible which had been the wharf for the colliery.

Returning to our cars we drove to Combe Hay for the afternoon’s walk. We started at a crossroads, not realising at first that there was a tunnel directly underneath. This had originally been a canal tunnel then was converted to a railway tunnel (now disused) by lowering the invert, underpinning the walls and building new walls and roof.

We then headed to the top of Combe Hay locks access and this is where things get compilated with the alterations that were made to negotiate the change in level.

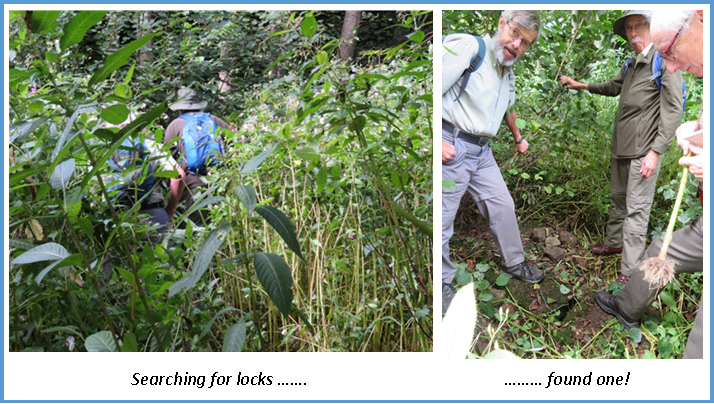

The locks 1- 15 all survive, some in reasonable condition some with erosion to the soft local stone, the top locks and site of the engine house are on the land of Caisson House, the owners of which had kindly given permission for us to view. The line of the locks passes in front of the house with the feeder and original canal running to the rear.

A Boulton & Watt pumping Engine fed the summit pound, the base of the engine house can just be made out in the undergrowth of Engine Wood.

At the Bull’s Nose – an extremely tight bend between locks 10 and 11 the canal leaves private land and a public footpath runs at the side down the side of the locks through the woods.

Reaching the road, lock 16 has been lost underneath a former railway embankment and after crossing the road the canal runs under the drive of a house. Beyond here apparently the locks are not in very good condition but we left the canal at this point as we’d run out of time. We returned through the village to our cars, the end of a very enjoyable and extremely interesting weekend. Set in beautiful countryside it’s easy to see how popular the restored canal would be to cruise. It is a long term project but the society are doing well in building relationships with landowners and protecting the line for future generations.

A huge thank you goes to all those involved, for the welcome we received and the wealth of information and knowledge imparted: Derrick for all his organisation and support, Patrick for the talk, Liz and Roger for being our guides. Also to Julian and his team and Neil at Claverton Pumping station.